- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

There has been much speculation about the future role of seafarers in the brave new world of autonomous shipping. But a new study suggests there's no need for alarm. GARY CROSSING reports…

Does automation threaten your job? Earlier this year, a Nautilus Federation survey found that 84% of maritime professionals believe that it does. However, a new report questions whether seafarers should be worried.

The research was produced by the Hamburg School of Business Administration for the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) with the aim of seeking to 'separate fact from fiction'.

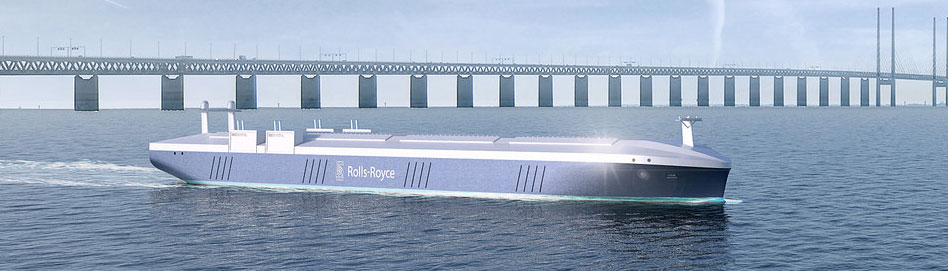

The report – Seafarers and Digital Disruption – examines the potential effects of the increased autonomy of ships, the digitisation and digitalisation of vessel systems, and the digital transformation of ship operations.

Its key finding is that even if as many as 3,000 autonomous or semi-autonomous ships are introduced by 2025, there will be 'no shortage of jobs for seafarers in the foreseeable future.'

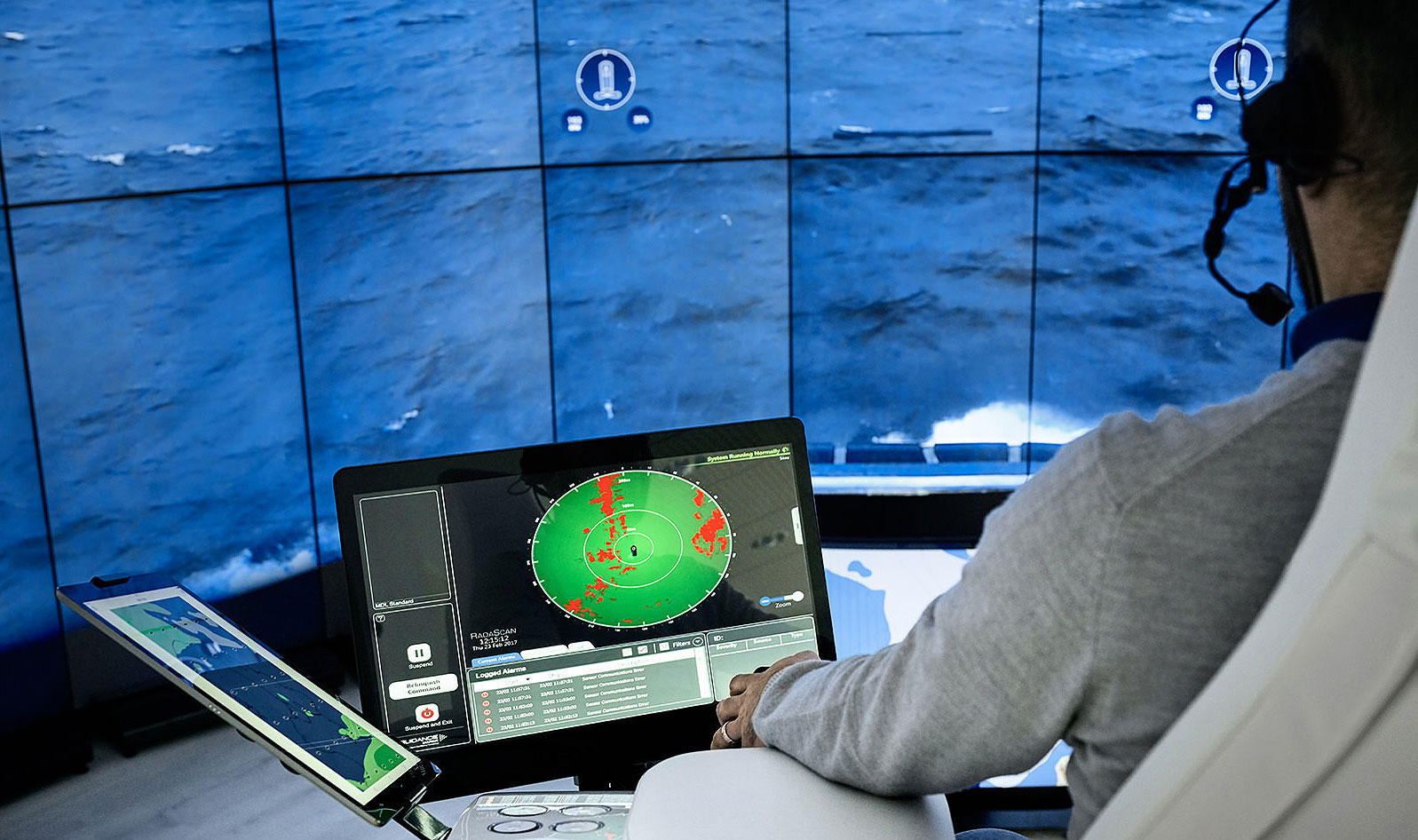

Rather, it argues, those jobs may alter. For while the increase in autonomous shipping may possibly reduce global demand for seafarers by between 30,000 and 50,000, at the same time it will increase the need for highly skilled remote-operators on shore, pilots of a new kind and riding gangs to keep high-tech ships operational.

The report paints a particularly positive picture for officers, claiming that they have 'no reason to worry about job security'. It contends that the predicted growth in the world merchant fleet over the next 10 years will continue the trend of a growing gap between officer demand and supply – with a forecast deficit of 147,500 officers by 2025, despite improved recruitment and training levels and reductions in officer wastage rates over the past five years.

So, while the digitalisation of ships may mean that the number of crew onboard a vessel falls, the increase in the world fleet will mean the need for officers will remain about the same. 'At the same time the number of "crew" on shore in supporting functions will increase, possibly significantly,' the report says.

‘This leaves valuable time to adapt training patterns and retrain experienced seafarers with digital competencies,’ it adds.

However, the researchers raised a number of important ‘human element’ questions for the industry to answer, noting how the traditional roles of personnel onboard and ashore will need to be redefined.

Owners and operators will need to determine what work needs to be done onboard and what work can be done remotely, identify which jobs will then become available and which qualifications will be needed.

'They will have to redefine roles, communicate, train and retrain their employees,' the study says. 'They will also have to carefully compare the commercial viability of technically disruptive projects.'

The industry also needs to determine how staff can be trained to obtain new skills and how existing skills can be passed on to a new generation in future – with a big question about whether compulsory sea time will remain relevant.

‘There is time to adapt training patterns and re-train experienced seafarers with digital competencies

Thought must also be given to the repercussions for industrial relations and collective bargaining agreements, the researchers warned. Decisions may have to be made on whether pay scales and pay logic need to be redefined.

The report says the legal repercussions of autonomous shipping also need careful consideration. 'Regulators need to define equivalency between human-driven action and machine-driven action.' it says. 'Particular thought needs to be given to essential notions like the "seafarer" if borders between shore-driven and board-driven vessels blur.'

The report cites the 2018 investigation by the Comité International Maritime (CMI) into the current regulatory environment for unmanned autonomous ships. The CMI asks several fundamental questions about 'what constitutes a ship, the possibility of a master who is not onboard, and the constitution of the crew'.

The whole concept of 'manning' is challenged by automation, the report notes, and there are significant consequences for the responsibilities of a master and the way that ships are regulated and insured.

Researchers also highlighted the need for attention to be paid to the future physical and mental welfare of seafarers. 'There are concerns that as the number of people onboard a vessel decreases, their functions are taken by machines and the physical demands decrease, mental demands will increase. This will result in less social interaction between those remaining, leading to issues like loneliness and potentially depression,' the report warns.

Noting the potential for minimum safe manning levels to be affected by automation, the report reassures that 'any adaptation of manning levels would be carefully filtered through international bodies and closely monitored by a variety of stakeholders. Work and rest hours would continue to be ruled by MLC, 2006, national legislation and collective bargaining agreements'.

The researchers also reflected on the concerns of seafarers from developing countries, who may find it difficult to get work ashore in their home countries should their jobs disappear with automation.

Tags